When you want to drink like F. Scott Fitzgerald in Rome,

go to - or avoid completely - the Hotel Quirnale, and don't punch the ticket inspector in the face.

A lot of places are making hay this year because of F. Scott Fitzgerald.

It has been 100 years since the great Gatsby was published. There are tours of Long Island and Paris, and guides to the Côte d'Azur, so people can go to the places he and Zelda frequented. His great-granddaughter, who is herself a very talented musician, is giving interviews. And people are rereading, or discovering anew, one of the greatest works ever written in the English language.

The Hotel Quirinale, in Rome, has been trading on his name for a while. They flaunt the fact that he stayed there, have drinks named after him (as well as opera stars - they are connected to the concert hall), and make sure that guests know that when they walk through these humble doors, the Fitzgeralds did the same.

The thing is, the Fitzgeralds apparently hated staying here, and, because Scott was drinking at the hotel before he was beaten up by Mussolini’s forces, they had terrible associations with it. This came out in his writing: in Tender Is the Night, Dick Diver sees his life fall apart it its suites before he is beaten by some taxi drivers and then the police.

Appropriately, one night, I was drinking vino sfuso and thinking about Hemingway and Fitzgerald, and how they really thrived in Paris, near Gertrude Stein. I thought about the beginning of A Farewell to Arms, and how it starts in Italy, and then I wondered if Hemingway had anything to do with Rome. It took a few seconds to remember that he had spent time in Milan; at this point in the trip, it was too late to go to the hospital where he had been cared for, but I liked to think we may have walked the same streets as he had when he was an unknown and injured volunteer ambulance driver. After a bit more research, it seemed that he didn’t have a lot of associations elsewhere in Italy. I looked to see if the Fitzgeralds had spent time in Rome, and found the Quirinale.

A few days later, I took the tram to the end of the line in the city center, and then a bus up to the hotel. There was an electric feeling as my fingers rested on the braille dots of the “Stop” button; it was a bit like a first date, anticipation added to uncertainty and then shaken up with a kaleidoscope of butterflies in my chest. Then my feet were on concrete and the bus wheels were scratching away towards the central station and I saw the glass awning stretched out over the street. My body felt a gravitational pull and I fell toward the foyer.

In Tender is the Night, F. wrote of the Quirinale: “they went through the deserted lobby oppressed by draperies holding Victorian dust in stuffy folds…” If you went just on that description, you could recognize this lobby out of a thousand in Rome. Say the street outside is loud with engines, crowded with jostling shoulders, the smell of exhaust and cornettos and the sourness of spilled beer and puddles of urine, bright sunlight slashing down from an unforgiving sun, the heat of an oven turned to “warm” painting your arms. Inside, it is like stepping into a marble version of a grandmother’s inherited quilt. There is a calmness, a peacefulness, a promise of mediocrity almost completely devoid of any elegance whatsoever. On the left: low seats with foam-stuffed cushions, occupied by two older women in flowered blouses purchased just for this trip so that they would look more Italian, solitary forefingers composing carefully on their phones. On the right: the reception, an unwelcoming open office with two concierges trying to avoid human contact; I passed them without any intimation of being either welcomed or challenged. In my memory, I was surrounded by the white of thin veneers of marble used indiscriminately over concrete columns and walls in a vain attempt at style, and the yellow of old wallpaper and upholstery that was originally pink, or perhaps even burgundy. This may not be the literal truth - the colors may have been different - but that’s the feel of the place: far past its prime, with no attempt to regain whatever had before passed for charm.

There were two hallways, left and right. I first walked left, but almost immediately came to an end; I paused to look at an odd glass display case offering custom-made tarot cards to wealthy visitors. In such a Catholic country, it struck me as odd that there were so many tarot card readers, but maybe I am misunderstanding both the Church’s attitude towards people who claim to be able to predict the future. I took a photo of the display to remind myself that I needed to look that up, and promptly forgot about it until writing these words. I turned on my heels and went back, taking the other hallway up a half-flight of stairs, lit by faux-gold lights, then turned left down a longer hallway. I saw the sign for the men’s room and thought: I don’t have to go, but I have to.

It was, admittedly, immaculate. There is a certain brilliance in well-kept public toilets, especially those that seem to be often maintained and rarely used. A part of it is that it is nice to be in any space that has a specific use and does not contain unnecessary distractions. People sometimes talk about the clarity that comes with travel, the feeling that one can focus on what matters; I often think it is actually the lack of distraction, the fact that our possessions and our surroundings are so often stripped to the bare essences of what we need, whereas our lives are crowded with the superfluous. For example, at home, our bathroom has small prints of cows, kids’ bath toys, my shaving brush and soap, an underwatered philodendron plant, liquid soap, bar soap, diapers, washcloths, an egg timer, books, a water bottle, two trash cans (I only just noticed the second one), two live-catch mouse traps (just found pushed back under the tub), and a Matchbox car wash, among other things. In the Quirinale men’s room, there were toilets, urinals, sinks, soap, and paper towels. Anyway, I didn’t really need to pee, but I went into the men’s room, and had the rush of thinking: nothing here has changed in the last 100 years. The toilets were ancient, but well-maintained; the tiles were worn, but in that way that indicates that they have been cleaned by hand by artisan cleaners; and the room smelled clean and unused.

If nothing else, I thought, I may have just peed in the same urinal, or at least the same room, that F. Scott Fitzgerald had peed in. Surely that must count as a win.

I walked out and continued on down the hall, then turned left again, at the back of the building. I walked down a short flight of stairs and, to the left, had an intense feeling not of déjà vu but of déjà lu. “There were five people in the Quirinale bar after dinner, a high-class Italian frail who sat on a stool making persistent conversation against the bartender’s bored: ‘Si…Si…Si,’ a light, snobbish Egyptian who was lonely but chary of the woman, and the two Americans.” The bar was there, but the only people in it were ghosts: the bar was not so much empty as abandoned - bottles askew or toppled, rubber drink lines disconnected and left in plain sight, a thick layer of dust begging for a child’s finger to draw in. I paused. Was this where I was supposed to get a drink?

A man in a tie and apron appeared, and I asked him: un bar o un caffè?? He pointed further back in the hotel, and I walked, almost dejected, thinking maybe the Fitzgeralds were right to be disappointed in the Quirinale - after all, one can’t judge a hotel purely on the basis of the toilets.

And spring exploded in front of me.

I read, a long time ago, that Cormac McCarthy’s The Road is all a long, depressing setup for one perfect, hopeful sentence. It felt as if the interminably drab hallways of the Quirinale were all a setup for the glory of its gardens. I emerged from the doorway into green, green, green, with a tiny bit of white and brown - the grass, the trees, the tables, and the glassware all shimmering in the sunlight. Picture a verdant lawn in a cobbled horseshoe on which were white tables and chairs placed just far enough apart that, when busy, conversations would blend into a murmur, with a long, well-stocked bar in the far left corner. I could see it in the evening in the 20s, bathed by soft yellow bulbs, a quartet in white jackets and black ties playing softly in a corner, the guests all dressed maybe not to the nines but at least to the sevens, as F. and Zelda emerged, their feet resting, for a brief moment, in the exact place I was standing, surveying their scene before a server showed them to their reserved table and a ripple went through the assembled guests. “The bar is in full swing, and floating rounds of cocktails permeate the garden outside, until the air is alive with chatter and laughter, and casual innuendo and introductions forgotten on the spot, and enthusiastic meetings between women who never knew each other’s names. The lights grow brighter as the earth lurches away from the sun, and now the orchestra is playing yellow cocktail music, and the opera of voices pitches a key higher…”

I could see it all.

Well, I could imagine it all; now, it was almost empty. If I hadn’t seen the couple at a table to the right sipping cocktails, and two men in ties behind the bar, I would have thought it was closed.

The men took my order together. One was a man, anyway; the other looked like he might have been 14, on his first job, and it was he who was unfortunately tasked with preparing my cocktail under the supervision of the twenty-something. In order to do so, he was first shown where the recipe booklet was kept next to the low fridge, then where the table of contents was, and how the recipe on the page was organized - with a photo of the finished product, as well as the ingredients and steps necessary to create it. I was told to find a seat, that they would bring it out to me, but I said that I was eager to see how they prepared it. The older one smiled, but the younger one forcefully avoided my eyes.

I was glad I stayed. In Italy, many people still buy fresh fruits and vegetables on the day they are to be used. They won’t buy a week’s groceries on Sunday, planning on using the peaches on Thursday; if they want a peach, they go out and buy a ripe peach, smelling and squeezing it. Americans, and the British, don’t have this sort of tradition. When we cut into an avocado, we can’t count on it being perfectly ripe; it may be a few days underripe, or brown and mushy, and the majority of us don’t really know how to predict which it will be. The Quirinale is Italian. When the teenager cut open the first lime, my heart stopped - I am used to yellowish flesh inside a green shell, but here, the inside was green as well, almost an aquatic green, a Mediterranean green, sunlight filtered through young leaves, each vesicle storing that light and then, when exposed, pouring the light out to whatever waiting eye might behold it. He cut the second lime, and it was the same; he then juiced both, and they walked down the bar a bit and I couldn’t see what they were doing, and then I was being served.

It was a citrus-heavy gimlet. Very citrus-heavy. I barely tasted the gin, and the sugar was so reluctant to greet my tongue that I wondered if he’d left it out. I smiled, winked, and thanked them.

I walked around to the far side of the lawn, by the fountain, to give the couple some privacy, and thought of Jordan’s preference for large parties because at small parties, there was never any privacy. I pulled out my notebook and pen and arranged the table, and heard a small laugh, and then heard…

Nothing.

It struck me that, for weeks, we had been surrounded by noise. Italian cities are cacophonous things, and Rome was particularly loud; suddenly, hemmed in on all sides by the high hotel walls, in the shade of old trees, sitting on a white chair with a white table on which was white paper and a white candle and a drink that was mostly lime and a bit of some type of distilled alcohol, I could hear myself move, the rasp of the gold nib against the laid paper, the tings of glasses being washed in a faraway kitchen.

The older waiter came over and asked me how my drink was. I told him it was delicious, that his kid was going to be a great bartender, and took the obligatory sip to prove my appreciation. Then I asked if this was the place with the most silence in Rome. He tipped his head to understand, then smiled and said possibly it was true.

Five minutes later, I realized I was wrong; there was far more gin in the glass than I thought, and I couldn’t write a damn thing. Instead I stared at the unflowing fountain, listened to the leaves in the gentle breeze, smelled something that wasn’t exhaust. Thought. I got to my last sip and then I was in the lobby; one of the receptionists was helping an older American woman with dyed fire-red hair read a map. I smiled at them and they didn’t see me. When I got to the bus stop, my head felt fuzzy. I settled into a window seat and pulled my camera out to take photos of the streets in the sunhot afternoon.

At the end of the line, some transit police got on the bus and checked everyone’s tickets. There was a brief flash when I met one of their eyes and I thought of hitting him, but it passed immediately and I gave him my card to scan. We thanked each other and he moved on, and I wondered how many people had, like me, spent an entire afternoon on getting a single, absurdly strong gimlet so they could better feel F. Scott Fitzgerald’s time in Rome, and then had consciously decided not to punch him in the face. Probably not that many, which is in some ways a damned shame.

And perhaps it’s a good thing I’m no Fitzgerald, I thought, as I got on the tram home.

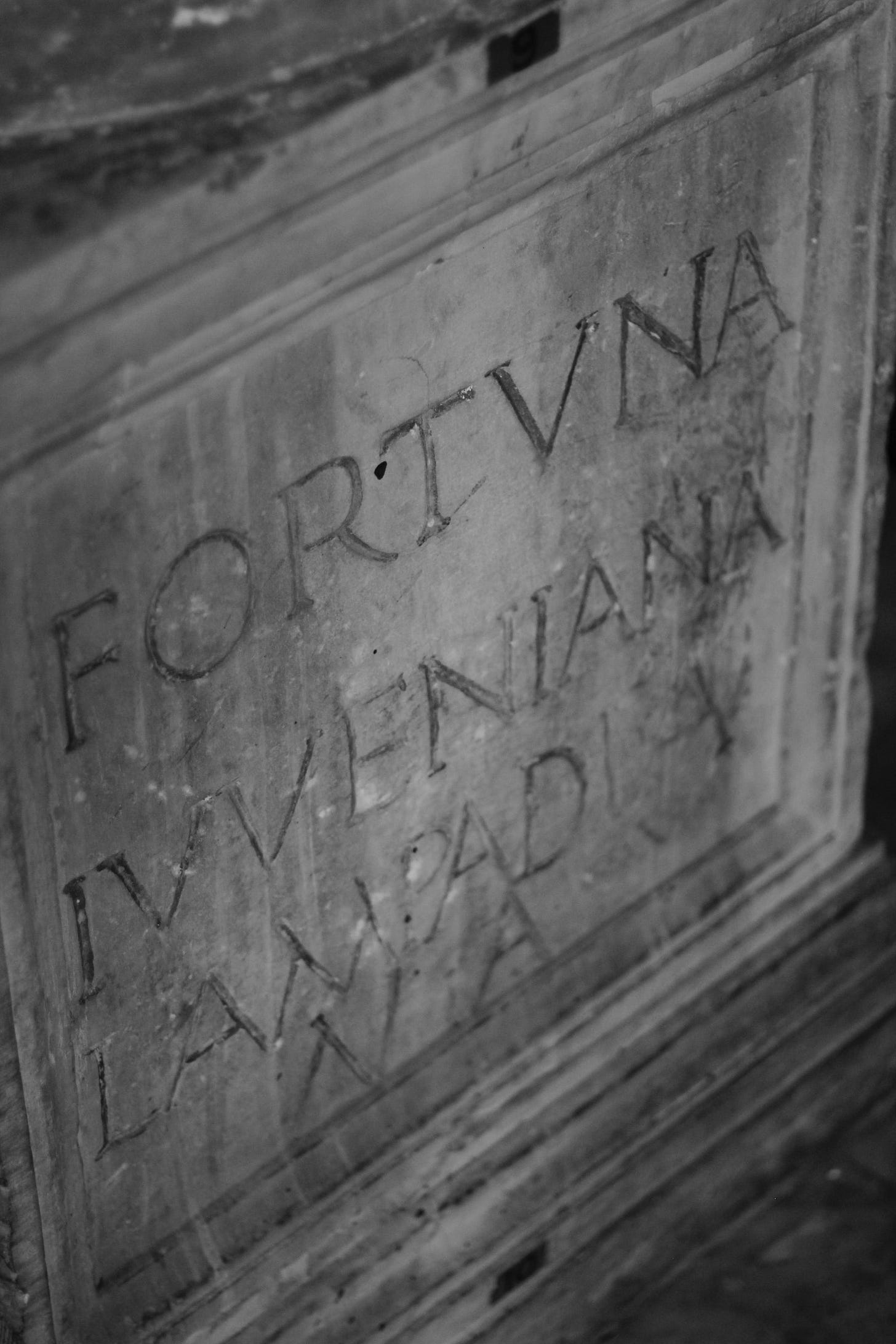

Lovely picture.

While living in Japan, a friend was getting married and his father travelled to Japan for the wedding. He was a fine Southern gentleman from North Carolina and he said of his son’s friends: “ You all remind me of characters from Fitzgerald.” To this day, I don’t know if it was a compliment or a put down.